Part

One:

The

Chosen People

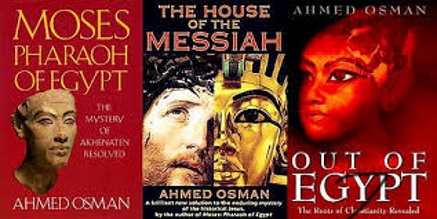

A Review of Ahmed Osman’s

Out of Egypt. The Roots of

Christianity Revealed

(Century, 1998)

by

Dr. Norman Simms of the

University of Waikato sent me a copy of this book, asking me to write a review

of it. This, my review, was originally published in his publication, The Glozel

Newsletter, No. 5:1 (ns), 1999, pp. 1-17. The following is a modified version of

this.

Part I: The Chosen People

Introduction

Another crucial peg in Velikovsky’s reconstruction was his identification of the biblical “Queen of Sheba” as Queen Hatshepsut, co-ruler with Thutmose III. Osman passes over this fabulous queen in a couple of pages (pp. 20-21), having far more to say about the influential Queen Tiye – whom Velikovsky argued to have been the prototype of the tragic Queen Jocasta of the Greeks (in Oedipus and Akhnaton). Osman identified Tiye all at once as – if I am still following him – Joseph’s daughter, Solomon’s “Great Royal Wife”, and Moses’ mother.

Controversial Bethesda pool discovered exactly

where John said it was

Ancient

History, Archaeology and the Birth of Jesus Christ

Part I: The Chosen People

Introduction

It is heartening to find scholars more and more

appreciating the importance of the east – Egypt being especially relevant here

– in influencing ancient and modern civilisations. M. Bernal (The Black Athena, 1987) took a big step

in this direction. Before him, Professor A. Yahuda (The Language of the Pentateuch in its Relation to Egyptian, 1933),

perhaps setting the ball rolling, had shown in minute detail – against ‘pan

Babylonianism’ – that the entire Pentateuch (first 5 books of the Bible) is

saturated with Egyptian influence: e.g. the distinct parallel between Egyptian

mythology and the patriarchal narratives of the Bible. Along these lines,

Bernal has referred to M. Astour’s view that the Greek story of Io-Zeus-Hera

closely resembles the Semitic one of Hagar-Abraham-Sarah (op. cit., p. 91).

Now Ahmed Osman, an Islamic author from Cairo,

has brought a twist to this recognition of the east by proposing some

astounding identifications in his book, Out

of Egypt (a reference to Matthew 2:15), in his attempt to show that the

roots of Christianity are to be found, not in Israel, but in Egypt. Osman

states the aim of his book when making reference to the destruction of the

great library of Alexandria by Christians in AD 391 (p. xii):

“As a result of this barbaric

killing of Alexandrian scholars and destruction of its library, which contained

texts in Greek of all aspects of ancient wisdom and knowledge, the true

Egyptian roots of Christianity and of Western civilization have been obscured

for nearly 16 centuries. The aim of this book is to rediscover these roots,

with the help of new historical and archaeological evidence”.

He goes on to write (next page): “The time has

come for Egypt’s voice to be heard again”. And he believes that he is the man

for the job: “Because of my Islamic background, I feel confident that I am

qualified to offer a balanced picture, which does not exclude any source from

examination”. Osman’s main sources are the Dead Sea Scrolls from Qumran (Dead

Sea) and the Gnostic literature of Nag Hammadi (Upper Egypt).

Perusing Osman’s book as a revisionist historian,

I find it fascinating that he has located David and Solomon precisely where

Immanuel Velikovsky did, to the early 18th dynasty of Egypt. No doubt

Velikovsky’s 18th dynasty revision (Ages

in Chaos, I and II) was his main achievement, that will stand in

pyramid-like strength after much else of his historical revision has collapsed

under the weight of scientific criticism.

The 18th dynasty is also Osman’s entire showcase,

encompassing all of his major characters. However, nowhere in his book do I

find reference to Velikovsky or to any other of the well-known revisionist

historians. Osman either has not been influenced by Velikovsky at all, or

perhaps does not bother to mention him because Osman retains the conventional

dating of the early-mid 18th dynasty, instead of lowering it by the 500-600

years that Velikovsky had maintained was necessary.

More radical still – and even the most intrepid

revisionists would baulk at this one – is Osman’s lumping together of Abraham,

Joseph and Moses, into the same 18th dynasty scenario, with, not only David and

Solomon (his Part I: “The Chosen People”), but even with Jesus (his Part II: “Christ

the King”); thereby totally ignoring customary chronological spacings.

According to Osman, the 18th dynasty characters: Thutmose III, Amenhotep III,

Yuya, Akhnaton and Tutankhamun, are to be identified as, respectively: David,

Solomon, Joseph, Moses and Jesus Christ. Thus, once traditional heroes of

Israel – even a great father-figure like King David – are now transmogrified

into Egyptian (or, in Yuya’s case, a Syrian). Osman’s excuse for so radical a bouleversement seems to be that he is

the one best suited to rediscover “the true Egyptian roots of Christianity and

of Western civilization”.

Well, I believe that he has gone about it all in

a most biased fashion. I cannot see how Osman – himself a follower of both

Sothic dating and Higher Critical view – can possibly escape the label of

anti-semitism (here meaning anti-Israel) as described in my earlier TGN article (“Velikovsky and Academic

Anti-Semitism”). Osman is guilty of historical piracy, ‘hijacking’ famous

Israelites into an Egyptian environment and ‘forcing’ Egyptianhood upon them.

But that is an old trick – the Greeks had done it (in favour of Greece) long

before him. Whilst admittedly the revision that has grown out of Velikovsky’s

efforts can be at times radical, its protagonists are generally careful not to

up-end established sequences. Much of the revision revolves around the more

plausibly allowable, like deleting ‘Dark Ages’, or shortening artificially

over-stretched eras (such as Egypt’s “Third Intermediate Period”). Velikovsky

in fact lost many supporters when he, flying in the face of hard archaeological

evidence, had indulged in such a radical up-ending by separating the 18th from

the 19th dynasty (sequentially) and inserting in between foreign dynasties of

150 years duration (his Ramses II and His

Time, and Peoples of the Sea).

Though Osman certainly becomes most interesting

when he departs from the conventional norm, this is only the case when he does

so with some sort of coherence. He correctly maintains that his country, Egypt,

exerted an influence upon biblical and Christian thinking. However, as I intend

to show, he does not appear to have properly understood what he has rightly

sensed. He tries to force his examples - thereby missing Egyptian influences

that really are there, whilst creating ones that are not.

The Sothic chronology lets him down badly,

exacerbating his mishmash.

Osman proposes David as an Egyptian pharaoh of

the C15th BC, who impregnates Sarai. And, taking his cue from the Babylonian

Talmud (Osman, p. 12), he recklessly makes David the father of Isaac. Despite

his avowed aims, Osman lets himself down by his failure to appreciate the

relevance of Egypt’s Old Kingdom; his lack of perspective regarding the 18th

dynasty; but, most of all, by his anti-Israel bias. He locates the era of the

Exodus to the 19th dynasty (New Kingdom), Late Bronze Age.

Professor Emmanuel Anati, a genuine

archaeologist, has argued authoritatively (in The Mountain of God, p. 287) that the entire socio-political

setting of the Moses story and Joshua’s Conquest pertains to the Old

Kingdom/Early Bronze Age.

That is centuries earlier than even the 18th

dynasty.

Osman adopts the view that the books of Genesis

and Exodus were very late compilations (cf. pp. 1, 12 and 66), having been long

handed down by oral tradition before being committed to writing during the

Babylonian Exile (C6th BC).

Here I should like to suggest, following P.J.

Wiseman (Ancient Records and the

Structure of Genesis), that the eleven toledôt

divisions throughout Genesis: “These are the generations of …” - as well as the

regular occurrence of catch-lines - attest Genesis as being a compilation of

family histories written on series of tablets, each history signed off by its

owner, or writer. The toledôt is the

classic colophon of ancient Near Eastern writings, but unfortunately read by

most as a heading instead of an ending. The Book of Genesis claims to be a

combination of histories for the great patriarchs, from Adam to Joseph. Moses

is traditionally its compiler or editor, hence the Egyptian flavour of the

entire book.

Osman does not give to the biblical date the same

credence as he applies to his other sources: Qumran and Nag Hammadi.

Osman, in fact, really butchers the biblical

chronology, showing scant respect for genealogical data and ensuing time spans.

He makes AD 391 a crucial, cutting-off point, his

point de depart.

He completely ignores what could be a vital fact,

that the library of Alexandria may have been totally destroyed by the Romans at

the time of Cleopatra, centuries before AD 391. Julius Cæsar is supposed to

have started that fire, to cripple the royal fleet (Dio Cassius 42. 38. 2).

Osman writes that the storehouse of old wisdom in

Alexandria’s Serapeum (p. xiii):

“…proved irresistible for

Diodorus Siculus … when he set out in the time of Julius Cæsar, to research his

ambitious Bibliotheca Historica - the ‘bookshelf of history’. Diodorus,

who was an enthusiast of the teachings of Hermes Trismegistus (which have

survived until today in the teachings of Islamic Sufis, Jewish Qabbalah,

Rosicrucians and Freemasons), became convinced of Egypt’s importance as a

source of knowledge”.

The Serapeum, Osman writes on the next page,

“later became also a center for Gnostic communities, both Hermetic … and

Christian”.

As I argued in a previous TGN (“Rediscovering

the Egyptianised Moses”, No. 4:6, 1998), Hermes was the Greek version of the

Egyptianised Moses. Also, Freemasonry is, like ancient Baalism, a syncretism of

Yahweh and Baal.

In Pt. II of this article, “Christ the King”, I

shall comment further on Hermeticism and Gnosticism.

No doubt revisionists reading Out of Egypt would

be thinking that they could propose identifications far more appropriate for

the biblical characters with whom Osman deals, especially Joseph (see #4

below); identifications, too, that leave intact detailed genealogies.

1. David = Thutmose III

Osman ‘becomes a revisionist’ when proposing that

pharaoh Thutmose III’s march via the narrow “Aruna” road was actually an

assault upon Jerusalem itself. This is an instance (about the only one) of

where he really grabbed my attention; not only because he, too, has suspected

that the Davidic era was synchronous with the early 18th dynasty,

but because his interpretation of Aruna had already been proposed and

strongly defended by Velikovskian modifier, Dr. Eva Danelius (“Did Thutmose III

Despoil the Temple in Jerusalem?”, SIS, Vol. II, 1978, pp. 64-79), after Velikovsky had laid the

groundwork by identifying Thutmose III as the biblical pharaoh “Shishak”

who sacked the Jerusalem Temple in the 5th year of king Rehoboam of

Jerusalem (I Kings 14:25) (Ages in Chaos, I, ch. iv).

No need here for Israelites to be turned into Egyptians.

Whilst Velikovsky’s “Shishak” argument was

ingenious, in part, he rather spoiled his own argument, I think, by holding to

the conventional view that the My-k-ty of the Egyptian Annals was

Megiddo in northern Israel. Dr. Danelius really saved this whole package by

identifying My-k-ty as pertaining to Jerusalem itself. She plausibly

identified all three roads debated as to their appropriateness by Thutmose’s

staff as roads in southern Palestine. The Aruna road that

Thutmose eventually elected to take – the road most dreaded by his officers –

was in fact the narrow and precipitous camel-road from Jaffa up the Beth-horon

ascent approaching Jerusalem from the north.

Osman has come to the same conclusion, that Aruna

refers to the Beth-horon pass. But, with his unfortunate identification of

Thutmose III with David, instead of the far more plausible “Shishak”, he

has introduced an unwieldy ‘baggage-train’ onto that narrow route.

2. Solomon = Amenhotep III

Another crucial peg in Velikovsky’s reconstruction was his identification of the biblical “Queen of Sheba” as Queen Hatshepsut, co-ruler with Thutmose III. Osman passes over this fabulous queen in a couple of pages (pp. 20-21), having far more to say about the influential Queen Tiye – whom Velikovsky argued to have been the prototype of the tragic Queen Jocasta of the Greeks (in Oedipus and Akhnaton). Osman identified Tiye all at once as – if I am still following him – Joseph’s daughter, Solomon’s “Great Royal Wife”, and Moses’ mother.

According

to standard biblical chronology, Queen Tiye would have to have lived in excess

of 800 years to have met all of these criteria.

Meanwhile

Velikovsky’s reconstruction of the Solomonic age had its own hiccups. He had

ventured to identify Hatshepsut’s 9th year expedition to Punt with the visit to

Jerusalem by Queen Sheba, but revisionist Dr. J. Bimson (in “Hatshepsut and the

Queen of Sheba”, SIS, Vol. VIII,

12-26) eventually destroyed this argument; so effectively in fact that many

‘Velikovskians’ who had already been badly shaken by Velikovsky’s proposed

separation of the 19th from the 18th dynasty, now even abandoned Velikovsky’s

18th dynasty matrix and began to explore new chronologies.

I

re-addressed the whole issue for C and CH

Review (“Solomon and Sheba”, 1997:1) and may have salvaged Velikovsky here

due to the fortuitous discovery (as I see it) of King Solomon himself in the

Egyptian records, in the person of the mighty and seemingly royal Senenmut; a

dominant figure during the co-reign of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III. Senenmut had

recorded of himself (P. Dorman, The

Monuments of Senenmut, 1988, p. 175): “I was in this land under

[Hatshepsut’s] command since the death of [her] predecessor …”. That, combined

with Senenmut’s information that his name “is not to be found amongst the

annals of the ancestors” (J. Baikie, A

History of Egypt, Vol. II, p. 80), suggested that he was originally not from

Egypt. A further possible hint that Senenmut was non-Egyptian were his

“idiosyncracies in regard to the Egyptian language: the uncommon substitution

of certain hieroglyphs” and his penchant for creating cryptograms, e.g., in

relation to Hatshepsut’s throne name, Makera (Dorman, pp. 138, 165).

Velikovsky

did not miss the point that the Queen of Sheba was known as Makeda in Ethiopian legend; a name

almost identical to Hatshepsut’s throne name, Makera (Maat-ka-re).

The visit

of Sheba/Hatshepsut to Solomon was essentially connected, I think, with her

marriage to king Solomon, occurring while Hatshepsut was yet queen. She would

soon become Pharaoh. Senenmut, who had unique prerogatives and who was favoured

with many titles, came to dominate Egypt at this time, despite the presence

there of formidable personalities like Hatshepsut and Thutmose. Most historians

would agree with Baikie’s view (op. cit.,

p. 81) that Senenmut “was by far the most powerful and important figure of

[Hatshepsut’s] reign”, and R. Hari’s, that few non-royal [sic] personages in

pharaonic Egypt “have caused as much ink to flow as has Senenmut” (“La

vingt-cinquième statue de Senmout” JEA 70,

p. 141). The fact that his statues and inscriptions are still so abundant in

Egypt is all the more remarkable considering the campaign of destruction that

was waged against his monuments after his death.

But historians

are not able to outdo the self-praise in which Senenmut himself (or his scribe)

indulges in his statues. “I was the greatest of the great in the land …”, he

announces on one (Baikie, op. cit., pp.

80-81). Due to Solomon’s profound influence on Sheba/Hatshepsut, the harsh

administration of Israel (cf. 1 Kings 5:13f.) spilled over into Egypt. Her

country, we are told, “was made to labour with bowed head for her …” (Breasted,

A History of Egypt, p. 271). And, not

surprisingly, Senenmut was the one whom she appointed in charge, “I was a

foreman of foremen”, he tells us, “… overseer of all the works of the house of

silver [treasury?] …. I was one to whom the affairs of [Egypt] were reported;

that which South and North contributed was on my seal, the [forced] labour of

all countries was under my charge”. As Solomon, Senenmut’s labour gangs spread

into Egypt and other countries. Given Senenmut’s tutelage over the young

Thutmose, I am not surprised – but rather grateful – to read where Osman has

picked up marked similarities between Solomon’s taxation system and that of

Thutmose III (op. cit., pp. 57-58).

Israel’s wisdom literature – much of which is

attributed to David and Solomon – began to be reflected in Hatshepsut’s Egypt.

I compared some of Hatshepsut’s inscriptions with Psalms, Song of Songs, and

other Scriptures; and I followed Baikie (op.

cit., p. 89) in noting that Hatshepsut had reproduced one of David’s Psalms

(131 Vulgate; 132 Jerusalem Bible) almost word for word in places, though

substituting “Karnak” for “Jerusalem”. Stratigraphically, the prosperous and

internationalized Late Bronze I-II seems to reflect the opulence of this time.

Thus there is no problem whatever with Osman’s correct assertion, in favour of

his own reconstruction (op. cit., p. 18):

“Indeed, no such empire [as David’s] can be said to have been created between

the reign of Tuthmosis [Thutmose] III in the 15th century BC [sic] and the

second half of the 6th century BC, when Cyrus of Persia conquered both

Mesopotamia and Egypt”.

The unexpected discovery of Solomon in the

Egyptian records seems to have further cemented Velikovsky’s 18th dynasty

scenario. The revision is now able to cope with the formidable trio of

Hatshepsut, Thutmose III and Senenmut, all in a biblical context.

Solon

A spin-off from this identification is that the

exceedingly wise Solon of Greek folklore who went travelling by ship for a

decade, notably to Egypt, for mercantile purposes, is most likely a Greek

appropriation of the wise Solomon in the latter part of his reign, when he

involved himself in foreign affairs and his fleet. There are strange anomalies

with Solon as a C6th BC Athenian. Archaeology does not seem to favour so

advanced a civilisation that early at Athens (see e.g. P. James, Centuries of Darkness, pp. 96-98). E.

Yamauchi (“Two Reformers Compared: Solon of Athens and Nehemiah of Jerusalem”, The Bible World, pp. 262-292) found it

doubtful if money was yet coined there, as Solon is supposed to have done; and

he also, following Cyrus Gordon (another great pioneer defender of the east),

has identified Solon’s reforms as Jewish, paralleling Nehemiah’s.

All of this strongly suggests that Solon was not

Greek at all.

The phenomenon that was Senenmut is perhaps

explained only by the revision. Akhnaton likewise is a phenomenon, and Osman

goes to great lengths to explain him.

3. Moses =

Akhnaton

Akhnaton stands out as a singular individual

throughout the history of Egypt, and it is not surprising therefore that

scholars are intrigued by him. Osman is no different, he being prepared to turn

chronology upside down to equate Akhnaton with Moses. Osman is not the first to

have noted a likeness between Akhnaton’s Hymn and Psalm 104, indicating a close

contemporaneity between Akhnaton and David – but this can better be met by

Velikovsky’s scheme according to which el-Amarna (Akhnaton’s era) is to be

re-located to the C9th BC.

And I think that Velikovsky’s equation of

Akhnaton with the legendary Oedipus, if correct, more than adequately accounts

for the Pharaoh’s personal idiosyncracies.

As for Moses, there is no need to repeat here all

that I wrote about him recently in my:

Moses - May be Staring Revisionists Right in the Face

identifying him as, among others, Sinuhe of the so-called Middle Kingdom

of Egypt. What I could mention here, perhaps, is Sir Flinders Petrie’s comment

about Sinuhe (Egyptian Tales, p. 129):

“The titles given to [Sinuhe] … are of a very high rank, and imply that he was

the son either of the king or of a great noble. And his position in the queen’s

household shows him to have been of importance … quite familiar [with the royal

family]”.

The Talmud, Osman says, holds that Moses was a

king (op. cit., p. 68). But a high

official of pharaohs would be more accurate.

El-Amarna [EA]

Perhaps Velikovsky’s finest reconstruction was

his detailed comparison between the EA letters of Amenhotep III and Akhnaton

and the mid-C9th BC. Describing himself as if a Time Lord, with “the searching

rod … of time measurement” in his hand, Velikovsky declared (Ages in Chaos, I, p. 224): “I reduce by

six centuries the age of Thebes and el-Amarna, and I find King Jehoshaphat in

Jerusalem, Ahab in Samaria, Ben-Hadad in Damascus. If my rod of time

measurement does not mislead me, they are the kings who reigned in Jerusalem,

Samaria and Damascus in the el-Amarna period”.

Chronologically, Velikovsky was not far off the

mark here. The ruler of Jerusalem (Urusalim)

during the el-Amarna period, Abdi-hiba,

identifies far better as Jehoram, rather than his father, Jehoshaphat,

according to revisionist, Peter James. I summarised this view in:

King Abdi-Hiba of Jerusalem Locked in as a ‘Pillar’ of Revised History

I have also accepted the conclusion of

Velikovskian modifiers, notably in this case M. Sieff, that el-Amarna’s

prolific correspondent, Rib-Addi,

could not have been king Ahab of Israel as Velikovsky had thought. On this, see

my:

Is El Amarna’s Rib-Addi Biblically Identifiable?

Peter James and his colleagues were far more able

to accept Velikovsky’s identifications of el-Amarna’s successive kings of

Amurru, Abdi-Ashirta and Aziru, with the biblical succession of

Ben-Hadad I and Hazael of Syria (“The Dating of the El-Amarna Letters”, SIS, Vol. 2:3, 1977/78, p. 80):

“With [these] two

identifications [Velikovsky] seems to be on the firmest ground, in that we have

a succession of two rulers, both of who are characterised in the letters and

the Scriptures as powerful rulers who made frequent armed excursions - and

conquests - in the territories to the south of their own kingdom …”.

And Dr. John Bimson clinched this by adding a

third Syrian king, Ben-Hadad II, the Du-Teššub of the Hittite records. (“Dating

the Wars of Seti I”, SIS, Vol. 5:1,

1980/81, pp. 21-22).

I think that we may be able to salvage Velikovsky

even further by finding his cherished Ahab, not in his choice of Rib-Addi (clearly a Phoenician king),

but in EA’s Lab’ayu. On this

tentative theory, see my:

“In most scholarly works Labayu is referred to as

the king or ruler of Shechem”, wrote D. Rohl and B. Newgrosh, adding “and this,

we feel, has been misleading” (“The El-Amarna Letters and the New Chronology”, C and C Review, p. 18, 1988, pp. 23-42).

Since Shechem is only a few miles from Samaria, I

suggest that Lab’ayu ruled from

there.

Was Lab’ayu

a Hebrew speaker? El-Amarna Letter 252, written by him, has been described by

W. Albright as “no less than 40% pure Canaanite” (“An Archaic Hebrew Proverb in

an Amarna Letter from Central Palestine”, JNES,

89, 1943, pp. 29-32); a comment that has evoked this response from Rohl and

Newgrosh: “It is a pity that Albright was unable to take his reasoning process

just one step further because, in almost every instance where he detected the

use of what he called ‘Canaanite’ one could legitimately substitute the term

‘Hebrew’.”

Albright indentified the word nam-lu in line 16 as the Hebrew word for

‘ant’ (nemalah). Lab’ayu wrote: “If ants are smitten, the do not accept (the

smiting) quietly, but they bite the hand of the man who smites them”. Albright

recognised here a parallel with the two biblical proverbs (6:6 and 30:25). King

Ahab likewise was inclined to use a proverbial saying as an aggressive

counterpoint to a potentate (cf. 1 Kings 20:10, 11).

Lab’ayu’s

son, too, Mut-Baal, also displayed in

one of his letters (# 256) some so-called ‘Canaanite’ and mixed origin words.

Albright noted of line 13: “As already recognized by the interpreters, this

idiom is pure Hebrew”.

“Son of Zuchru”

Velikovsky also identified king Jehoshaphat’s

captain, “son of Zichri”, with el-Amarna’s “son of Zuchru” (Ages in Chaos, I, pp. 228-230). Who

could argue with that!

Queen Jezebel

Velikovsky had ingeniously identified the only

female in the el-Amarna correspondence, Baalat-neše,

with the biblical “great woman of Shunem”, whose son Elisha restored to life (2

Kings 4:8-37) (ibid., p. 220). But I

think that, given Baalet-neše’s

undoubted rank, a likelier candidate for her would be Ahab’s wife, Jezebel

(i.e. Neše-bel-[at]?). On this, see my:

Is El Amarna’s “Baalat Neše” Biblically Identifiable?

Kingdom of Mitanni

Many historians – though not Osman, who passes it

over in one page (p. 56) – have puzzled long and hard over the so-called

‘Kingdom of Mitanni’ that figures in the el-Amarna correspondence.

What were its origins? Where was it located?

Its language – as with the name of its best-known

king, Tushratta or Dushratta, who wrote to the el-Amarna pharaohs

– is thought to be Indo-Iranian. But once again the revision may provide the

key to unlock the enigma. DUSHRATTA would simply be a variant of the name,

Abdi-Ashirta (i.e. AbDU-aSHRATTA). He is Ben-Hadad, Ahab’s contemporary. See

my:

Ben-Hadad I as El Amarna’s Abdi-ashirta = Tushratta

The name therefore is probably not Indo-Iranian

at all, but West Semitic; the last element being the name of the Canaanite

goddess Ashtarte. The name DU-TEŠŠUB is a similar construction, substituting

for Ashtarte the storm-god Teshub. The mysterious ‘Kingdom of Mitanni’ turns

out to be simply the extensive Syrian kingdom of Ben-Hadad I and Hazael, a

buffer state between Assyria and the Hittites.

4. Joseph = Yuya

Osman maintains that Joseph was the highly

credentialled Yuya, Syrian relative

of Akhnaton. Yuya, like Joseph, he

states, was the only official in Egypt ever to be called “Father of Pharaoh”.

And he optimistically claims that the details of Joseph’s life after his

interpreting Pharaoh’s dreams “are matched by only one person in Egyptian

history - Yuya, the minister of

Amenhotep III (p. 39). But again Osman’s apparent ignorance of pre-18th

dynasty Egyptian history lets him down. Professor A. Yahuda (op. cit., pp. 23-24) had already found the

equivalent title, “Father of Pharaoh” in Old Kingdom Egypt; the Genesis

expression, ab, ‘father’, a title borne (centuries before Yuya) by the Vizier, Ptah-hotep, who was

itf ntr mryy-ntr, ‘father of god, the beloved of god’; god

here indicating Pharaoh.

Now, since Ptah-hotep was also a wise sage, whose

writings resemble the Hebrew Proverbs, and since he – like Joseph – lived for

110 years, then it is worthwhile considering - as some scholars already have - that

Ptah-hotep was Joseph in his guise as scribe and sage.

Osman’s identification of Joseph is a classic

example, I think, of where revisionists would think that they could easily

trump him. T. Chetwynd, for instance (in “A Seven Year Famine in the Reign of

King Djoser with Other Parallels between Imhotep and Joseph”…” C and AH, 1987,

pp. 49-56), has found numerous parallels between Joseph and the celebrated

Vizier, Imhotep, of the 3rd dynasty (Old Kingdom), who supposedly

saved Egypt from a 7-year Famine.

Imhotep, who according to J. Hurry (Imhotep, p. 90) was “one of the few men of

genius in the history of ancient Egypt … one of the fixed stars of the Egyptian

firmament”, is portrayed as a kind of ‘Leonardo da Vinci’ of Egypt:

mathematician, scientist, engineer, architect. He was more besides. Carved on

the base of a statue of Zoser in the Cairo Museum is a short inscription

describing Imhotep as: “The seal-bearer of the King of Lower Egypt … the high

priest of Heliopolis ... the chief of the sculptors, of the masons …”. Imhotep

has also come down through history as a thaumaturgist, healer and Egyptian

patron saint of medicine.

Joseph also, according to Yahuda (op. cit., p. 24), would have been “of the high

priestly caste” of Heliopolis – like Imhotep. Chronologically, 3rd

dynasty Imhotep is perfectly situated in relationship to my 4th

dynasty Moses connection. (Refer back to my Moses article).

Concluding

Remark

Really, the presence of Israelites in positions

of great power even in Old Kingdom Egypt is my answer to Osman’s belief in the

Egyptian roots of the Chosen People. It was in fact a Hebrew influence that

permeated Egypt and then came back to Israel. Would not Jacob have carried all

of the treasured toledôt scriptures of his forefathers into Egypt, where

they would have been handed on to the influential Joseph? He, as priest of

Heliopolis and Vizier of Egypt, would have preached them to the Egyptian

people. The theology of Heliopolis became pre-eminent in the land.

Imhotep-Joseph was one of the real geniuses of Egyptian history.

Now we are beginning to understand why the early

Old Testament reflects such an Egyptian influence. Some of its writers, Joseph,

Moses and Solomon, were also key figures in Egypt’s destiny. Strictly speaking,

the influence was from the side of Israel. Thus, Osman might have found rather

more fertile subject matter had he chosen to write about Israel’s influence,

rather than Egypt’s, upon ancient to modern culture. But his prejudices

weighing against that may be too strong.

Part Two:

Christ The King

Part II: Christ

the King

Predictably, now, Osman tries to ‘pour’ the Holy

Family also into an 18th dynasty matrix; with Jesus as Tutankhamun;

Mary as Nefertiti; and Joseph as the Vizier, Aye. Here again

one encounters the emergence of various questionable patterns of argument that

clearly and strikingly parallel those in Part I. Osman again:

- places a blind trust in the conventional chronology and archaeology.

Whilst the historical era of the four Gospels,

once revised, might – and only might – turn out to be relatively more clear cut

by comparison with events in early Egyptian dynastic history, one should

nevertheless expect the chronological earthquake caused by Velikovsky to be

still transmitting aftershocks right down the line, so as to plunge late BC

events into an AD time frame. Moreover if Solon really is Solomon, as I

maintain, and the ‘Ionian’ philosophers actually have their origin with Old

Testament Joseph, and Athenian archaeology is not properly established before

the late C5th BC, then Classical history – Greek, and Roman, too –

must stand in need of a significant revision.

Of course I would not expect Osman to be able to

produce a new model just like that. My problem with him is that he so

uncritically embraces conventional late BC dates (e.g. for Herod and Pilate) as

“the established historical facts” (Out of Egypt, p. 110). Chronologically, Osman seems

to work hand in glove with Hershel Shanks, editor of the influential

Washington-based magazines Biblical Archaeological Review and Bible

Review, of whose conclusions I was so critical in The Glozel Newsletter (No

4:2, 1998).

- he treats with contempt the four Gospels.

Osman’s refusal to consider the Gospels as being

significant eyewitness records is to my mind another classic example of what I

noted in Pt. I, that not a shred of

credibility ought to be conceded to the writings of Israel. He seems unaware of

the papyrus discoveries from Egypt and Qumran that, according to German

papyrologist, C. Thiede (Eyewitness to Jesus, Doubleday), call for an

earlier dating of all four Gospels. {According to the article “Thiede’s Witness”,

in The Wanderer (June 12, 1997), this book is now very hard to find.

Is there being applied by the academic world a “Conspiracy of Silence” -

to use the title of Osman’s ch. 17 - in the case of Thiede? And of Carmignac?

(see below)}.

Shanks’ reaction to the new scholarship is the

typically off-handed sort to which entrenched academics must resort whenever

they cannot cope with the facts (Wanderer, ibid.): “Highly regarded

scholars are often reluctant to spend the time it takes to debunk these far-out

claims”. Well, it is not “the time” that they lack, but the answers.

An ironical note: I doubt if the

Egyptian-oriented Osman would be over-impressed by the fact that: “… Hershel

Shanks puts Thiede in the same category as those cranks who claim that Jesus

was not Jewish but Egyptian”.

Thiede’s conclusions may not be mainstream, but

they accord nicely with those of expert linguist, J. Carmignac (The Birth of

the Synpotic Gospels, Franciscan Herald Press, 1984), who discovered many

links with the New Testament whilst translating the Qumran texts. Carmignac was

in fact “absolutely dumbfounded to discover [how] extremely easy” it was

for him to translate back into Qumranic Hebrew the Greek texts of Matthew and

Mark (ibid., p. 1). This

led him to the inescapable conclusion that Matthew and Mark were originally

written in Hebrew (or possibly its sister-language, Aramaïc), thus according

with “numerous Fathers of the Church” that there was “a Hebrew Matthew”.

Carmignac felt compelled thus to revise the dating for the synoptic Gospels (ibid.,

pp. 6, 60):

.… The latest dates that can be admitted for Mark (and the Collection

of Discourses) is 50, and around 55 for the Completed Mark; around 55-60 for

Matthew; between 58 and 60 for Luke. But the earliest dates are clearly more

probable: Mark around 42; Completed Mark around 45; (Hebrew) Matthew around 50;

(Greek) Luke a little after 50.

In support of this revision, Carmignac provided a

most striking example from Luke 1:68-79 of the Evangelist’s dependence upon

what he entitled Semitisms of Composition (pp. 27-29): “Is it by

chance”, he asked, “that the second strophe of this poem begins by a triple

allusion to the names of the three protagonists: John [the Baptist], Zachary,

Elizabeth? But this allusion only exists in Hebrew; the Greek or English

translation does not preserve it”.

Dr. Eva Danelius, whom we met in Pt. I in

“Did Thutmose III Despoil the Temple in Jerusalem?”, SIS, Vol. II

(1978), claimed for instance that the Book of Revelation (conventionally dated

to c. 95 AD) ought really to be viewed from a pre-70 AD standpoint:

For the attentive reader it is

obvious that a part of John’s visions – the 24 elders, the importance of clean

white garments, the punishment of those who neglect their duty as watchmen –

reflect details of the duties of priests and Levites in the Beth Moked, the

northenmost building of the Temple compound, where the keys to the Temple mound

were guarded under measures of the strictest security (p. 70, with reference to

the Babylonian Talmud, Ch. 1. Midoth).

- he is quite biased in his methodology.

Osman employs a convenient modus operandi throughout especially the

latter part of his book, sweeping aside as “fiction”, or “forgeries”,

whatever documents oppose his viewpoint. Thus the entire Book of Joshua

becomes “a work of fiction” (p. 168) because – according to Osman’s

extraordinary thesis – Joshua should no longer by then have been alive. And whatever

early AD documents do refer to the physical Jesus – contrary to Osman’s

argument that there was no physical Jesus that late – must be dismissed out of

hand by him as “forgeries”, without any backing up of his claims with

solid evidence or footnotes.

Just as the mainstream archaeologists, basing

themselves upon a faulty chronology, end up finding no Old Testament biblical traces

(e.g. of the Exodus; the Conquest; David/Solomon), and need to dig deeper, so often,

too, with the New Testament, which critics accuse of being ‘un-historical’,

with ‘later additions’. Until one digs deeper. Here is a classic case in point (https://opentheword.org/2014/09/02/controversial-bethesda-pool-discovered-exactly-where-john-said-it-was/):

Controversial Bethesda pool discovered exactly

where John said it was

written by Dean

Smith

….

The remains of the Bethesda Pool found exactly

where the Apostle John said it was located.

There is a story in the Gospel of John that proved

problematic for liberals who don’t believe the Bible.

I am talking about Jesus healing of the lame man

at the pool of Bethesda (John 5:1-15). In the account, Jesus came across a lame man

lying by the pool. According to tradition, when an angel stirred the waters,

the first sick person to enter the pool was healed.

When Jesus asked the man, who had been lame for 38

years, how he was doing, the man said because he did not have anyone to help

him, when the waters stirred someone always stepped in before him. Jesus said

to him, “Get up, pick up your pallet and walk” (v 8) and the man was instantly

healed.

In the account, the apostle John provides some

detail about the pool. First he said it was near the “sheep’s gate” and

secondly it had “five porticoes” (verse 2). A portico, similar to a porch, is a

covered entrance way. It was a five-sided pool.

However, because the healing by this pool is only

mentioned in John’s Gospel, the liberals quickly concluded it was a later

addition by someone not familiar with Jerusalem. That theory prevailed until

the late 19th century when archaeologists discovered the pool exactly where

John said it was — by the Sheep’s gate now located in the Muslim-controlled

sector of Jerusalem.

Not only that, the pool had five porticoes, just

as John said it did. It was five sided because the rectangular pool had two

large basins that were separated by a wall/portico. This made five in total for

the pool. The northern pool collected water which replenished the southern

side.

Because of the broad steps located beneath a

portico leading down to the southern basin, it is believed this pool is also

served as a mikveh or ritual bath for the Jews.

In addition, they even found evidence of the

healing tradition associated with the pool as they discovered shrines dedicated

to a Greek god of healing — Asclepius (a god of medicine/healing). It was part

of a Roman medicinal bath built on the site between 200AD and 400AD.

Obviously, pagans recognized the healing

attributes of the pool and transferred them to their pagan gods. A similar

thing happened in Acts 14:9-18 when villagers in town of Lystra mistakenly

believed Zeus

and Hermes had performed a miraculous healing after Paul and Barnabas

healed a lame man from the city.

So John was right.

Osman’s ‘Jesus’

(i) As Tutankhamun

Osman has to make much of Tutankhamun, whose tomb

inscriptions rather than the four Gospels, he seems to think, hold the true

account of Jesus’ fate. He calls the young Pharaoh “the charismatic

Tutankhamun”, adding (p. 135): “It is, I believe an unconscious recognition

of the truth about his identity that impels millions to visit his tomb … each

year in what might be described as a form of pilgrimage, and more millions to

queue for hours to view … the treasures recovered from the tomb by Howard

Carter …”.

Or, one might wonder, may not such fascination be

due to the fact that people just love to view magnificent treasures of gold and

lapis lazuli?

The truth is, as P. Fox wrote: “… curiously

enough, for all the splendour of his burial, Tutankhamun was a ruler of little

importance” (Tutankhamun’s Treasure, OUP, 1951, p. 20). And H. Carter,

the discoverer of Tutankhamun’s tomb, wrote similarly (The Tomb of

Tut-ankh-Amen, I, 45):

In the present state of our

knowledge we might say with truth that the one outstanding feature of

[Tutankhamun’s] life was the fact that he died and was buried. Of the man

himself – if indeed he ever arrived at the dignity of manhood – and of his

personal character we know nothing.

Dr. Velikovsky had used the supplementary (as he

saw it) information of the Oedipus drama to help him account for

anomalies of this period, such as why so insignificant a king as Tut

(Velikovsky’s Eteocles) was glorified with so magnificent a tomb by Aye

(his Creon) (Oedipus and Akhnaton, Abacus, 1969, Ch. “Crowned

with Every Rite”, pp. 131-141).

Not at all convincing either is Osman’s forcing

of Egyptian texts and the Bible to support his theory that ‘Jesus’/Tutankhamun

was killed by an 18th dynasty priest, Panehesy, so as to tie in with

his interpretation of the Talmud, according to which a priest, “Pinhas

… killed [Jesus]” (b. Sanh, 106b, as cited by Osman, p. 132). Osman reaches the new

conclusion – without offering any primary evidence in support – that

Tutankhamun was killed by Panehesy; who, as Akhnaton’s “chancellor and Chief

Servitor of the Aten”, may indeed have been a priest. He then really

complicates matters by identifying Panehesy, firstly with the Israelite priest

Phinehas (Numbers 25:6-15), before going on to equate both priests with the

Talmudic Pinhas. But nowhere does he bother to show where the Talmud

identifies this Pinhas as a priest.

The names Panehesy and Phinehas are indeed

strikingly similar [the name Phinehas is clearly of Egyptian origin],

but their circumstances are not. The zealous Phinehas had intervened when an

Israelite had, in flagrant breach of the Law, brought a Moabite woman into his

family “under the very eyes of Moses and the whole community of the sons of

Israel as they wept at the door of the Tent of Meeting”. Phinehas arose,

“seized a lance, followed the Israelite into the alcove, and there ran them

both through, the Israelite and the woman, right through the groin” (vv. 6-8).

This incident is said to have occurred in Transjordania, not “at the foot of

Mount Sinai” where Osman would have ‘Jesus’/Tutankhamun meet his violent death.

To get around this inconvenient snag, Osman – taking his cue from documentary

theorist, E. Sellin (Osman, p. 144) – argues that the biblical account of

Phinehas has been “subjected to some priestly sleight-of-hand in the editing in

order to cover up what actually happened”.

This neat piece of subterfuge sets Osman free

then to pursue his own far-fetched Whodunnit.

(ii) As

Joshua

Osman also equates Jesus (Hebrew Ye-shua) with Old Testament Joshua (Ye-ho-shua), enabling him to synthesise

the episodes of Moses and Joshua on Mount Sinai (Old Testament) with the

Transfiguration (New Testament), with Moses and Jesus together on the same

mountain (for him also Mount Sinai). But here Osman quite undoes himself:

- firstly, by adhering to the traditional view that Mount Sinai was

Jebel Musa in the Sinai Peninsula (he calls it Gebel Musa, p. 101). [Egyptians

may understandably be reluctant to let go of the centuries long tradition of

having a ‘Mount Sinai’ in their own (or neighbouring) territory]. Professor

Emmanuel Anati (The Mountain of God: Har

Karkom, Rizzoli, 1986) had proved Jebel Musa to be quite lacking in Late

Bronze Age archaeology (relevant to the 18th dynasty). Osman will later have

St. Paul trekking off to Jebel Musa, thus enabling him to develop further his

pro-Egyptian thesis, with the Apostle supposedly being influenced by

Alexandrian Hermetic and Gnostic thinking. But his case for Paul’s dependence

upon Alexandrian lore cannot be sustained given that Mount Sinai could not have

been anywhere near Egypt. St. Paul says that Mount Sinai was “in Arabia”

(Galatians 4:25).

- secondly, as if that weren’t bad enough, his reconstruction leads

him into the absurd situation whereby his ‘Jesus’/Joshua, who had already been

slain, later resurfaces in the Book of Deuteronomy; not to mention – after that

– in what Osman calls “an entire book devoted to his exploits” (Book of Joshua)

(p. 168).

Joshua/Jericho

Archaeology’s original impulse was to recognize

the Early Bronze Age walls at Jericho as the famous fallen walls of the Book of

Joshua. But that notion was abandoned once the Sothic scheme of chronology was

applied to the site, re-dating those particular walls to about half a

millennium earlier than Joshua. Osman naturally swallows this line of

reasoning, calling the entire Book of Joshua “a work of fiction” (p. 169). The

fact is that the book has in support of its narrative a complete stratigraphy.

Jesus

Osman claims that the physical Jesus is not

referred to in contemporary records, either Roman or Jewish. I say physical

Jesus because a key distinction in Osman’s thesis is that Jesus had both (a) a

physical persona, as Joshua/Tutankhamun; and (b) a spiritual persona, as known

by the Apostles (p. 109). Osman is even bold enough to claim that, in this very

convenient (for him) split theory – which has something of a Docetist ring

about it [the Docetists denied that Christ ever had a real body or a narrowly

‘historical’ existence] – he is supported by the Church Fathers. But from my

reading of the Fathers, I think that Osman has badly misunderstood their use of

allegory, according to which all the holy men of the Old Testament were to be

regarded as forerunners – in one way or another – of Christ; but not as the

actual Christ; just as they regarded the holy women (e.g. Sarah, Ruth, Judith

and Esther) as types of Mary.

In the minds of the Church Fathers (e.g. Sts.

Irenaeus, Adv. haer., III, 22, 4;

Epiphanius, Haer., 78, 18; Jerome, Epist., 22, 21), Jesus Christ and Mary

were the ‘New Adam’ and the ‘New Eve’, and they believed the Old Testament to

be replete with symbolical prefigurations of the two. Osman, referring to the

physical Jesus, writes (p. 109):

Two thousand years ago, at the

time Jesus is said to have lived, Palestine was part of the Roman Empire. Yet

no contemporary Roman record exists that can bear witness … to the physical

appearance of Jesus. Even more surprising is the absence of any reference to

Jesus in the writings of Jewish authors living at that time in Jerusalem or

Alexandria ….

I think that there is a bit of legerdemain involved here as well. It is

all too easy for Osman to say “no contemporary … record exists”, when he is

going to, one by one, dismiss as “forgeries” any contenders, and brush aside

the Gospels as contradicting each other (p. 110). Contemporary Jewish historian

Flavius Josephus wrote, not only about the Essenes - and about Pontius Pilate,

John the Baptist, and James - but he also wrote directly about Jesus Christ (Antiquities of the Jews, Bk. 18, ch.

iv):

Now, there was about this time

Jesus, a wise man, if it be lawful to call him a man, for he was a doer of

wonderful works – a teacher of such men as receive the truth with pleasure. He

drew over to him both many of the Jews, and many of the Gentiles. He was (the)

Christ; and when Pilate, at the suggestion of the principal men amongst us, had

condemned him to the Cross, those that loved him at the first did not forsake

him, for he appeared to them alive again the third day, as the divine prophets

had foretold these and ten thousand other wonderful things concerning him ….

Osman claims that this passage, “greatly valued

during the Middle Ages as the only external testimony from the C1st AD pointing

to Jesus having lived at that time” has since “become an embarrassment, having

been exposed in the 16th century as a forgery” (op. cit., ibid.). He offers not a single name or footnote to verify

this, only an argumentum ab silentio,

that the prolific Origen never referred to this passage.

Re the supposed contradictions amongst the four

Gospels, Osman [who believes that the earliest versions were written only

“several decades after the events they describe”] writes (pp. 109-110):

… when we attempt to match the

four gospels … against the facts of history we cannot escape the implication

that with the gospels themselves we are dealing with a false dawn. We find no

agreement about when Jesus was born or when he was put to death.

… Only two of the four gospel

authors, Matthew and Luke, refer to the birth of Jesus, but their accounts do

not agree. … Matthew places his birth firmly in the time of Herod … Luke …

relates the birth of Jesus to that of John the Baptist, who was also born ‘in

the days of Herod, the king of Judaea’ (Luke 1:5).

…. Luke goes on to tell the

familiar story of the birth of Jesus in a Bethlehem stable … and contradicts

both Matthew and his own earlier account by placing these events a decade after

the death of Herod the Great: ‘And it came to pass in those days, that there

went out a decree from Caesar Augustus, that all the world should be taxed.

(And this taxing was first made when Cyrenius (Quirinius) was governor of

Syria). … We know from Roman sources that this event could not have taken pace

before AD 6, the year in which Quirinius was appointed governor of Syria and

Judaea became a Roman province.

Of course the Roman people themselves did not

date in terms of BC or AD.

Scholars and historians would be reluctant today to

assert that the date for Jesus’ birth has been fixed with chronological

precision. John Paul II, for instance, writing his first encyclical “Redemptor

Hominis” (1978), referred to the date of the Jubilee Year 2000 “without

prejudice to all the corrections imposed by chronological exactitude …” (#1). I

am very much impressed with the work of Daryn Graham on this controversial subject

area. See e.g. his:

Osman, after conveniently sweeping aside all

opposing data, will direct our attention towards what he calls “the established

historical facts”. But while such an authoritative sounding phrase might be

enough to coerce many into an immediate passive conformity, it probably does

not have that sort of hypnotic effect upon hardened revisionists, who might

straightaway ask: “What “facts”? How “established”?

As with the Old Testament, so with the New, it is

easy to point out anomalies with the conventional history; but then to go on

and say that the writings of Israel contradict real history, or one another,

because they do not fit the Procrustean bed of textbook chronology, is to say

too much – until that bed has been properly made and set on solid foundations.

There is enough evidence in the case of Jericho (Tell es-Sultan), for example,

to indicate that establishment figures such as Hershel Shanks are not reliable

guides as to archaeological interpretation.

And certainly Ahmed Osman does not inspire much

confidence in this regard.